Godel's incompleteness theorems : how much can we know?

For millenia, people have needed a way to discover truth and knowledge about the world. Aristotle gathered his thoughts on the matter in a series of works named The Organon. The title translates as “The Instrument” and conveys a sentiment of accuracy and reliability a subject that was previously much less formal and even sometimes twisted by the sophists who were eloquent speakers but did not care whether they arrived at the best answer.

Since then logic has played a central part in the development of Science and Mathematics, and is still used informally in everyday life to decide what is right or wrong. Logic has become pretty much universal, in Sciences few could argue against the simple efficacy of a logical argument. Over time, logic grew in complexity and power. It is now a well-researched branch of mathematics and is also at the heart of the construction of mathematical arguments, both a means and an end. Mathematics and logic surround us and are seen as this higher authority, though few explore the foundations on which our knowledge is built. Aristotle used the word “Instrument”, but these days with the rise in popularity of artificial intelligence it seems more fitting to talk about logic as a mechanism. Let’s go ahead and see where drawing this parallel between machines and reason takes us.

The proof

At the core of logic is the formal proof. It is a sequence of sentences in formal language. The

formal language is simply the language in which a sentence can be expressed.

A sentence is written as

A formula’s Truth value depends on a variable and they are written as follows:

In order to determine whether the proof is valid or not, we will resort to axioms (sentences that are always true) and inference rules (a mechanism through which a sentence can be deducted from one or more preliminary sentence(s) known as premise(s)). We will refer to a combination of a formal language, a set of axioms and inference rules as a formal system.

This is what a formal proof might look like in natural language :

In this example we have taken “All beings are made of atoms” and “Reggie is a being” as axioms of our system, and the inference rule we used is simply the fact that if a property is true for all members of a class, then it must be true for a particular member.

And there we have our first proof. The point here is not to argue about the truth of the axioms but more so to determine whether a proof is valid or not. This is of course not a purely mechanical proof. A complete specification of axioms and inference rules as well as the language would take several pages, not to mention building a mechanism to verify it! Even in papers, a common knowledge of the formal system is assumed for brevity’s sake.

A very brief history of Formal Systems

From the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, many mathematicians worked on formalizing Set Theory. The effort could be said to have started with Georg Cantor, credited with the invention of Set Theory, and includes work by mathematicians including Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell as well as Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel who gave their name to ZF(C) (Zermelo-Frankel set theory) which is still in use today.

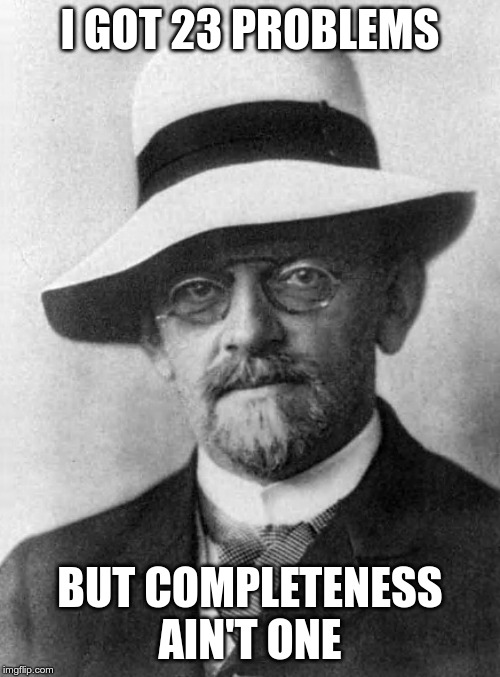

When in the year 1900 the mathematician David Hilbert published a list of 23 problems {% cite hilp —file godel_incompleteness %}, the notion was that with a suitable formal system, all of the statements in mathematics could either be proved right or wrong. This is what we call completeness. In fact, Hilbert’s 10th problem asks for a construction of the solution for a specific class of equations, the Diophantine equations, assuming that there had to be such an algorithm.

In his second problem, he also asks for a proof of the consistency of the axioms of arithmetic, meaning whether it would be impossible to prove a sentence in arithmetic and its opposite. The promise of finally filling the gaps in mathematics seem to have appealed to young Kurt Gödel and he started his PhD with the intention of contributing to Hilbert’s dream.

Gödel numbering and representability

This paragraph contains some mathematical notation necessary to explain how the incompleteness theorems came to be. If that’s not your cup of tea, go ahead and skip to the First Incompleteness Theorem section

Besides consistency, there is another notion which is central to understanding Set Theory: representability. A weakly representable set has a corresponding formula. A given integer is in the set if and only if we can prove the formula to be true for that integer. This essentially implies that there is a method to enumerate all elements of the set, but we might not necessarily be able to prove that an element is not in the set.

To enable talking about logic within the language we introduce Gödel numbering, the association of any formula of the formal language with a natural number. This is today quite intuitive as anything we represent in a computer is in binary code. Let us not explain exactly how this is done and assume that there is such a mapping. More interestingly, proofs are also represented as numbers…

We will define the code of a formula as . All the rules of logic can then be transposed as functions of the Gödel numbers, even the inference rules. One key consequence of this is that we can decide whether a sequence of statements is a valid proof using arithmetic!

With that knowledge, let us go back to Set Theory. The question of whether a number is in a set could be answered by proving that a specific formula is true for .

{% raw %} {% endraw %} Here we have introduced several notations: is the formal system that we’re working with, and is a formula that has a value of True or False for every integer, and corresponds to the set . Here, indicates that it is possible to prove that is True with the axioms and inference rules of . The symbol indicates the provability of for all elements of the set . This property is known as weak representability and is very important for what follows, as it establishes a bridge between Set Theory and the formal system.

We can now use formulas as arguments of other formulas thanks to Gödel numbering. We could for example define the set of all provable sentences, and find a nice formula that can only be proved to be true for the Gödel number of provable statements (formulas). We define provability as a formula of the language!1

The Diagonalization Lemma

With Gödel numbering, we can now write equivalent formulas, but using numbers as representations of formulas! We can use that strange loop in mathematics to find a formula’s special “fixed point” sentence. The diagonalization lemma tells us that for any formula we can construct a sentence such that:

That sentence’s provability is inextricably linked to ‘s true value. If is provable, then is true, and if it is false then is not provable. Applying this to the negation of the provability sentence described earlier yields the first of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems.

Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem

Assuming is a formal system with sufficient arithmetic2 then we can construct a sentence of the language of such that is true but not provable. In other terms, we have a sentence that says the following:

We could try to prove this sentence. But if we succeeded that would mean the sentence would be provable which contradicts its very meaning. The sentence would then be False and we cannot prove False sentences. Is it False then? We encounter a similar problem when assuming the sentence is False, since that would again lead us to proving a False sentence. Seeing as we assumed that the system was consistent, that sentence is not provable, not False and therefore it must be True.

Gödel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem

We have proven that consistency of the system implies that the Gödel sentence is true but unprovable. The second theorem is about consistency and is linked to Hilbert’s second problem. It was noted that if a system can prove its consistency, then it must also be able to prove the Gödel sentence .

- can prove

- Gödel’s first theorem: implies that is true

From 1. and 2., we can deduce that if can prove then can prove . By contradiction, we can then conclude that consistency cannot be proven.

Incompleteness vs Decidability

Later in the twentieth century, Alonzo Church and Alan Turing took a similar approach to prove the undecidability of First Order Logic.{% cite hopcroft —file godel_incompleteness %} A theorem that there is a mechanical way to verify is called recursive. Of course if a theorem cannot be proven, then it can hardly be verified mechanically. On the other hand, for a specific set, there might be a way to enumerate elements of the set, but there might not be a general, mechanical way to verify (prove) that a particular number belongs to the set. One example of such a problem is the Halting Problem. It is defining the set of programs that terminate. Of course, it is possible to build an infinity of programs that satisfy this definition, but for a specific program it is not always possible to know if it will, like a program that looks for integers that satisfy Fermat’s last theorems. A system is called decidable if all of its theorems (sentences derivable in it) is decidable. Incompleteness of a system implies its undecidability but there are many cases where a system is complete yet undecidable. Gödel himself showed that there are complete systems in First-Order Logic, yet First Order Logic is undecidable.

Humans vs Mechanisms

Some would see these theorems as a fundamental flaw, an acknowledgement by mathematics of its own shortcomings, though there really is nothing wrong with probing the limits of our tools for reasoning. Beyond Gödel’s sentence which might seem a specific edge case that should not be allowed, there are “reasonable” cases that are not provable and even more that are not computable. So is there something missing in our system? Is there any system at all with sufficient arithmetic capable of completeness? Based on the discussion we just had, it would seem a mathematician is capable to find a sentence to be true where formal systems are not able to prove them. Therefore no formal system can be devised that encompasses the mathematician’s knowledge or general human intelligence.

Though what struck me as I examined the consequences of the GITs, is that we actually used logic to come to the incompleteness results. Indeed they are just another set of theorems, inferred from our definitions of provability and notations related to Gödel numbering. We have found that we cannot always prove the truth, yet on that journey we used the very system that we are trying to understand better. The incompleteness theorems are now just another tennet of mathematics, upon which we can expand and prove more and more theorems.

The incompleteness theorems are just stating a system’s limit, assuming the system to be consistent. Any “logic machine” could verify that proof, and there is no mysterious human factor that sets us apart from that machine.

This mathematical introspection had a major influence in the development of computer science. In fact formal systems were a central of artificial intelligence research in its early days. However this approach sometimes labeled as Good Old Fashioned Artificial Intelligence (GOFAI) has shown its limits in terms of practicality. In these systems, a gigantic number of axioms and definitions is needed to arrive at a conclusion in all but the most basic of practical cases. In recent years, AI has experienced a resurgence of interest, due to availability of data and hardware and using non-deductive methods (neural networks, statistical inference). Of course the decisions we arrive at using these methods aren’t as clean-cut as when using a formal system. And as we design machines with higher and higher power of abstraction, it is important to remember, neither they nor us will know everything.

References

{% bibliography —file godel_incompleteness %}

Footnotes

-

For the sake of brevity, we’ll have to take the existence of that formula as given ↩

-

Sufficient arithmetic means that it contains axioms that allow us to do arithmetic. The minimum set of axioms are Robinson Arithmetic for the First Incompleteness theorem and Peano Arithmetic for the second ↩